FROM THE SOLOIST

The concerto for viola and orchestra by my dear friend and colleague Patrick O’Malley represents all that is exciting about composing for the viola as a solo instrument. He uses the complete range of the instrument and explores a vast array of emotions and hues. When I first listened to Patrick’s orchestral work Rest and Restless, I was immediately drawn to his creative palette and, while there are nods to the great composers like Debussy, Bernstein, and Copland there is something so incredibly fresh in his writing. I was thrilled when he agreed to compose a concerto for me, and it is one of my absolute favorite concertos for viola. Giving the world premiere in Fort Wayne and now recording it with the wonderful BBC Scottish Symphony and Andrew Constantine has been a complete joy, and it is with great satisfaction and a deep sense of thanks and privilege that this amazing work can now be heard worldwide. - Brett Deubner

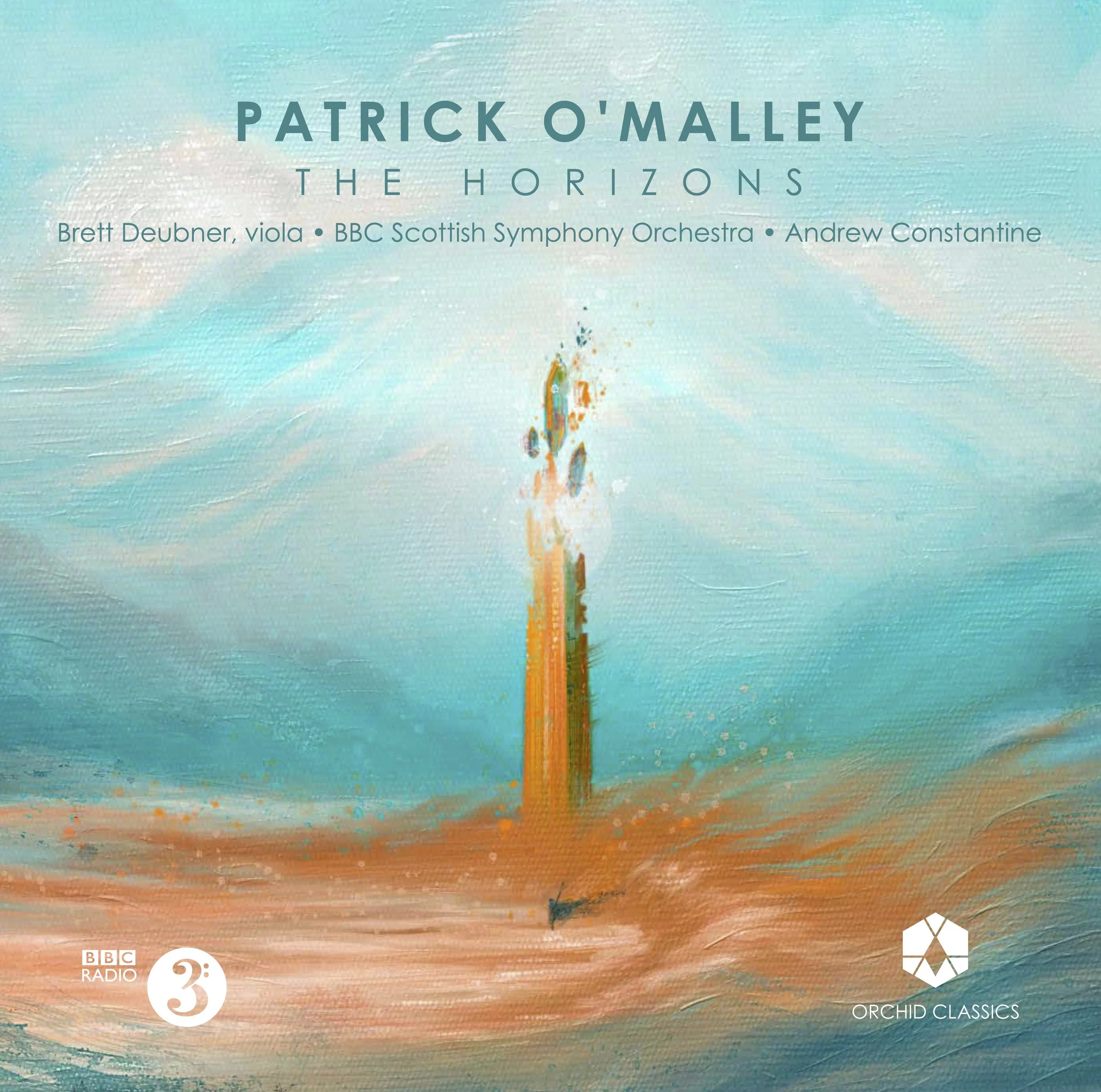

The Horizons

VIOLA CONCERTO

SOLILOQUY

OBLIVIANA

REST AND RESTLESS

Brett Deubner, viola - BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra - Andrew Constantine

available from Orchid Classics, 2024

“[the Viola Concerto] is a most effective new addition to the none-too-large solo repertory for the alto voice of the string family… O’Malley does a masterful job of exploring the various registers of the instrument and engaging the soloist in various contrasting moods and gestures during the course of the freely tonal Soliloquy… I found this tone poem [Obliviana] most effective and rewarding… Rest and Restless yields a masterful combination of sonorities, gestures, and polished orchestration that leaves the listener most satisfied. Performances, recorded sound, and presentation of the CD all leave nothing to be desired except a high recommendation from my quarter.”

- Fanfare Magazine

Recorded at City Halls, Glasgow, Scotland on 4-6 September 2023

Recording Producer: Andrew Keener

Recording Engineer: Dave Rowell

Assistant Engineer: Caitlin Pittol-Neville

Editor: Stephen Frost

Album Artwork and Score Covers: Angela Bermúdez

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Director: Dominic Parker

Orchestra Manager: Richard Nelson

Orchestra Librarian: Julian de Ste Croix

BBC Studio Guarantee: Alison Rhynas

Orchid Classics Director: Matthew Trusler

Special Thanks to Ryan Baird, Donald Crockett, David Alan Miller, Michael Repper, Cristian Măcelaru, Osmo Vänska, Andrew Norman, Sean Friar, Christopher Theofanidis, Steven Mackey, Kevin Puts, Adam Borecki, Carolyn Ule, Kelly Kasle, Danny Leo, Robert Alexander, Tyler Eschendal, Dan Caputo, Corey Dundee, Peter Shin, Stephen Cabell, Jon Senge

FROM THE COMPOSER

During the course of my musical endeavors, I have occasionally been confronted with the question “Why write for the orchestra?” The answer may at first seem immediately self-evident: it is an incredibly rich ensemble of many different instruments capable of an infinite variety of emotional and intellectual expression, as demonstrated by its substantial canon of works in the classical, theatrical, and media genres. And yet, practicality does perhaps insist on a deeper, more personal justification. Composing (and preparing) an orchestral piece tends to be a huge amount of work, to say nothing of the difficulties in getting an orchestra to perform one’s composition when there are already such quality works it can choose from the canon previously mentioned. In addition, learning to compose for orchestra, despite all of the literature and courses available on the subject, often feels like a perpetual business of trial and error compared to the more immediate feedback of working in chamber music or electronic music production. What can the orchestra do, that other means of music-making cannot, that keeps us writing for it?

I can only speak for myself in this regard, but in addition to the typical advantages of the orchestra (large emotional range, variety of color, virtuosity etc.), I have come to think of it as an ideal medium with which to explore “juxtaposition” and “balance”. As an artist I have often felt a sense of being pulled between multiple worlds: a 21st century composer interested in musical expression rooted in previous centuries, a composer writing in both classical and media music (often very different mediums), a composer brought up in the rural Midwest now working in the endless cityscape of Los Angeles… This has given me a strong (but not negative) sense of “in-between-ness” which has led to often writing pieces that set up different musical worlds and then see how they interact, repel, and coexist. The orchestra gives one both the freedoms and constrictions with which to explore these concepts effectively if not passionately, deriving expression, form, and journey from placing musical characters and feeling in both opposition and parallel. This approach hopefully leaves the audience with a personal sense of meaning, even if the piece in question is largely abstract. The constitution of the orchestra itself personifies this idea with dozens of individuals playing wildly different instruments, creating a sense of cohesion, community, and balance.

The works presented on this album all deal with the juxtaposition and combination of concepts in some way. The viola concerto concerns itself with rejuvenation and maturation; frozen wanderings evolving into bright futures embodied in the image of a grand horizon. While composing the piece in 2022, at the same time coming out of the Covid lockdowns, I felt a strong feeling of capturing this sense of “rebirth” with the concerto, using Brett Deubner’s immense lyricism on the viola to explore a world of both fragility and strength. Even simply beginning to write the piece required me to momentarily abandon the sophistication of my studio and keyboard: having struggled for days to find a satisfactory beginning, it was only when I stepped outside onto the balcony and began to sing to myself (that primordial method of music-making) that a simple three note pattern emerged with the sound of flutes, and subsequently became the backbone of the majority of the work. The concerto’s beginning also focuses on a micro-duality of static pitch versus melody, with the soloist playing nothing but icy C sharps for the first three minutes before “awakening” into song. Even at this point, the soloist and orchestra do not so much play together as trade off material for almost the remainder of the movement, further exploring a contrast of an individual versus a group. You may very well hear further juxtapositions throughout the work, if not discover some on your own that were rather unconscious on my part. The scherzo (my favorite classical form for dualities) finally combines the soloist and orchestra into a mischievous adventure, using a shining, march-like trio section to suggest a brief respite on the journey. The adagio features the most focused music of the concerto (itself a juxtaposition against the rest of the work’s explorations and energies), from which the music springs forth with the determined finale, gathering a sense of graceful strength that was absent from the preceding movements. I am grateful to Brett for suggesting that we include my solo piece Soliloquy as an encore to the concerto, showcasing his remarkable gift for expressive playing, and the beauty of the viola in isolation.

The remaining half of the album is a true “B-side” in the sense that, while the concerto deals with juxtaposition in a very classical way, Obliviana and Rest and Restless explore juxtaposition with the more extreme side of my voice. Obliviana was conceived primarily out of anxieties and curiosities regarding rapid technological advancement (I was in elementary school when the internet came to our house) and how it compares to “disconnected” states of living. This manifested as enormous, slow-moving chords that break down into chaos, followed by a child-like march of clicking and shining, steadily advancing into the unknown future. In some ways the piece also deals with “rebirth” as the viola concerto does, but filtered through harmonies and images of a science fiction dystopia rather than a virtuoso soloist, and with a more stark comparison of stable and unstable musical ideas. Listeners will hear this most blatantly at the end of the piece when, after several minutes of contrapuntal, multilayered orchestration, the music momentarily converges on a single very loud, intentionally out of tune G sharp in the brass, throwing into question the refined preceding material.

Rest and Restless on the other hand has more terrestrial concerns. Born out of a solo double bass composition, the music moves back and forth between quietly prickly ideas (usually focused in the low register), versus an optimistic (and eventually triumphant) theme that spans the whole range of the orchestra. While writing the original bass version, I remember thinking about how many “slow” movements in classical music are often the most intense emotionally (occasionally even getting fast!), which was fascinating to explore through a bass player’s ability to hauntingly surf between high harmonic notes and low, booming open strings. This large outline of range is what convinced me to “fill in” the piece with orchestration, while keeping several moments of solo writing to preserve the piece’s roots. The term that I keep coming back to when describing Rest and Restless is “emotional landscape” due to its navigation of polarized feelings in the orchestra, as well as my own emotional responses while creating the music.

And speaking of navigating this music, I am enormously grateful to Brett Deubner and our conductor, Andrew Constantine, for championing these works, as well as their passion for making this album a reality. Working with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, along with concertmaster Bradley Creswick, director Dominic Parker, and librarian Julian de Ste Croix was an immense pleasure, and you will hear their conviction throughout this record resounding from the dreamlike venue of City Halls Glasgow. Credit for that lovely sound equally goes to our producer Andrew Keener and engineer Dave Rowell, who well understand this music and were wonderfully collaborative and supportive (I learned a lot from watching them work). My hope is that all these musicians’ efforts will leave you with a sense of why I continually find the orchestra worth writing for. - Patrick O'Malley